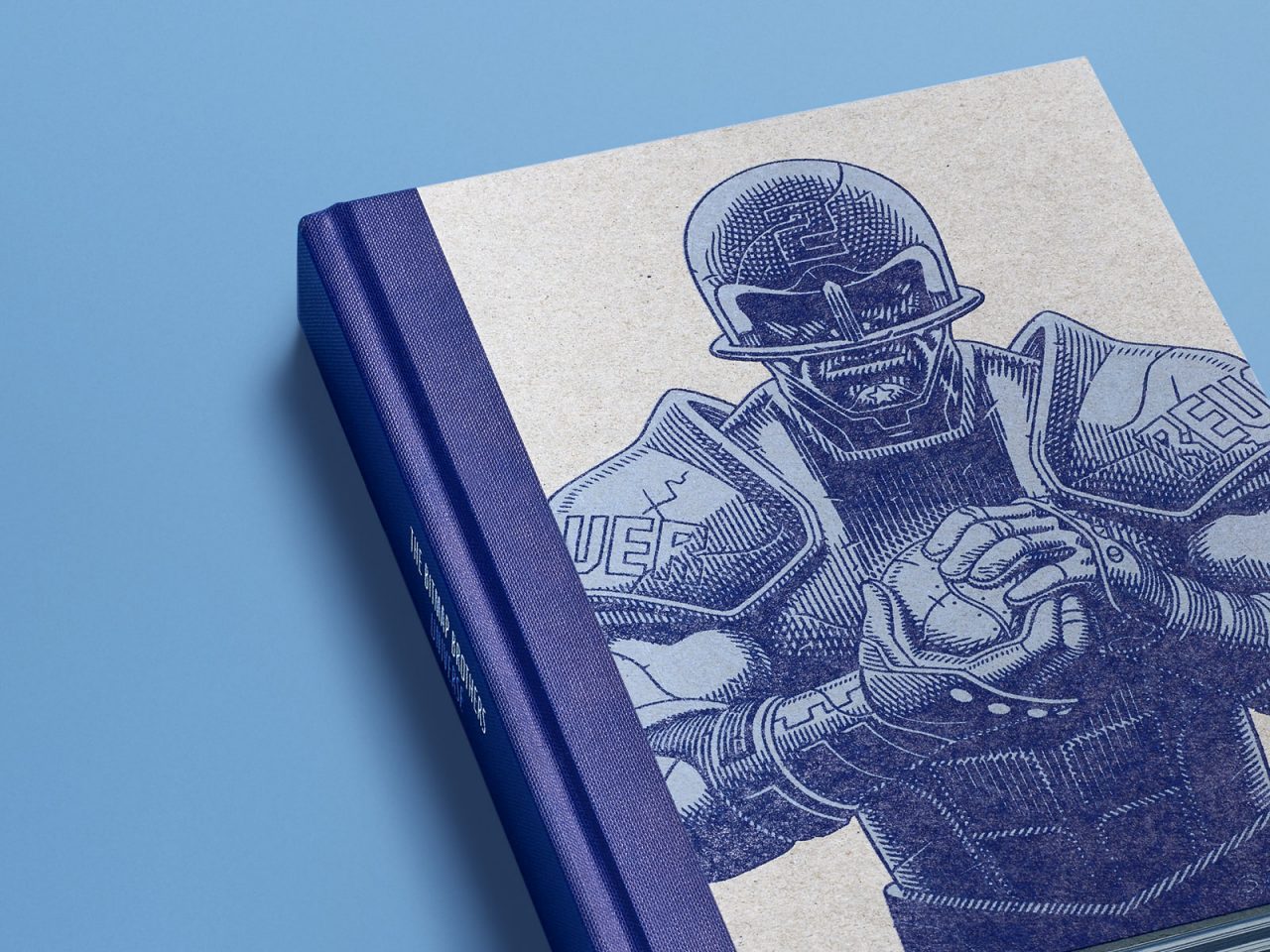

The Making of Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe

The craft and perfectionism behind The Bitmap Brothers’ defining futuresport game

When you wake up being masturbated by a great big horny gorilla, you’d best look like you’re enjoying it. So advises Thundercrack!, a pornographic black comedy horror B-movie, one of many weird fables to pass through London’s notorious Scala Cinema during the late 1980s. Another tells of hooligan futuresports, luxurious dungeons, and happenstance worthy of a godlike piston-powered computer. Let’s start at the beginning.

Daniel Malone spent his time at Ipswich Art College arguing with all but one of his teachers: the typography tutor who let him draw comicbook characters in class. Not that he didn’t like the subject, she understood, but he already had two masters in superhero artists Jack Kirby and John Buscema.

‘Batman was the first guy I drew,’ Malone explains, ‘but Marvel is my biggest influence. But so little of it existed then that you often had to draw something if you wanted to see it – and I wanted it, so I drew and drew and drew.’

Exposed to American editions of The Fantastic Four by his dad, prolific commercial artist Jerry Malone, Dan’s childhood favourite was astronaut-turned-granite-skinned-clobberer the Thing. After Marvel UK launched The Mighty World Of Marvel in 1972, its first British weekly, Malone never missed an issue. He was bemused, though: its characters, once iconic, now lacked charm and definition. Not for another 50 issues did he realise his mistake: MWOM was a reprint, its stories dating back to the 1960s. That’s when it clicked.

‘Kirby, the king, had evolved his style to have this graphic rock-like look for the Thing, and it was a pure, natural evolution of him just drawing the character over and over again. That was magical. I never forgot it.’

Neither Marvel nor Britain’s own 2000AD were hiring when Malone left college a decade later. A brief stint at underground publisher Knockabout Comics offered work but little pay, and even worse if it was ‘a bad month’.

It was his loyal typography tutor who spotted an ad in media digest Campaign. It seemed that someone did need a ‘2000AD-style artist’.

Armed with a thick portfolio of extra-curricular college work, the graduate Malone was ‘thrilled just to be in London, in King’s Cross, right in the heart of it. Well, more in the armpit, with fucking crowds of smack dealers outside by the snooker hall. But The Scala was great, brilliant. You had to run the gauntlet just to get in the place.’

Up its incongruous fairytale tower he went, to rooms adjacent to its ‘cinema of sin’. Malone’s roughhouse style satisfied marketing director Pete Stone, and the job of professional artist was his.

The studio proper was on the next floor down, where he was introduced to his new desk, his new colleagues, and— wait, what was with all the keyboards and monitors?

‘Oh, so you’re doing computer games, then!’ realised Malone.

When they weren’t making games like Cauldron and the infamous Barbarian, Palace’s people would climb the stairs behind the Scala’s auditorium and watch its whacked-out panoply of movies and moviegoers.

This was Palace Software in 1985, which, Malone remembers, was just after Live Aid. ‘I had no interest in computer games,’ says Malone. ‘I’d come all the way up to London for a job interview I thought was for comics.’ But whatever, he gave it a try, stumbling not only into the game industry’s first wave of dedicated artists, but also into one of its true pioneers.

He continues: ‘If you look at games companies at the time, Palace was very artist-led. They wanted to make the artists’ ideas work. That was “what the programmers were there for.”’

‘They showed me a running version of Cauldron on the ZX-81, and I thought it was just some rough demo. “Is this the finished game?” It looked basic, almost crude. I realised I’d have to scale down everything I was doing. When I did the character Tal for [The Sacred Armour of] Antiriad, he was two 8×8 sprites on the Commodore 64. The sprite editor we used meant we had to draw him in two halves and stick him together. I had to draw him out on paper first, actually draw these big pixels on a bit of graph paper just to design the character.’

Thus begins the journey of what Lionhead Studios creative director Gary Carr considers ‘the best pixel artist in the world, no question.’

In total, Palace Software would incubate four future Bitmap Brothers: Malone, Carr, audio wizard Richard Joseph, and designer-coder Sean Griffiths. Carr recalls:

‘It was a cool company. We felt we were doing something edgy. We were part of a film company and had interesting people everywhere.’

That would be an understatement.

When they weren’t making games like Cauldron and the infamous Barbarian, Palace’s people would climb the stairs behind the Scala’s auditorium and watch its whacked-out panoply of movies and moviegoers: the Laurel and Hardy appreciation society Sons Of The Desert; the owners of the occasional latex glove found in the aisles after lesbian all-nighters; and, Malone remembers, ‘this cat that used to walk around on its hind legs.’

Malone was an avid skateboarder, and would often ride across The Scala’s invitingly tiled floor. The Scala, in return, would infiltrate the studio and its games, as the artist recalls:

‘Stanley Schembri used to get really angry at his computer and literally burn it with a lighter and aerosol. The keyboard caught fire once and he chucked it out of the window, into Pentonville Road.’ Sean Griffiths also remembers lead programmer Richard Leinfellner letting his C64 go – this time from the roof. Seared into the memory of journalist Gary Penn, meanwhile, is Schembri and Malone’s visit to Commodore User:1

‘Stan was off his fucking— He and Dan came up in his Mini. We’d all been drinking, and probably worse, when Stan decided to drive us around London, off his rocker, with the door open and waving this stick, pretending he was blind. I probably literally shat myself.’

Palace was moving into 16-bit development when Malone, somehow still alive, first encountered The Bitmap Brothers. It was a trade show demo of Xenon. ‘Arcade-style! Sharp! Not the bloody great Lego bricks of the C64!’ he gushes. ‘I was hungry for some of that 16-bit stuff.’ Months later, the Bitmaps’ Speedball became the lunchtime diet at Palace. Its taste, thought Carr, seemed familiar:

‘We were an artistic company but the Bitmaps went a level further. They were pushing the art style during what was initially an 8-bit timeframe. We had great games at Palace, but one didn’t necessarily look or feel like another, or feel like it was from the same brand. The Bitmap games came from a stable: they had things you recognised instantly, certain ways of applying light and colour. This was the early days of making computer games and it was pretty organic, but they were designing from the ground up. Dan had that same integrity.’

‘I was an artist alongside him, and we were peer-level artists, but I couldn’t sit in the same room in terms of ability. He could hide pixels when pixels were like bricks. He could turn a 16-colour palette into a 256-colour palette. He could do effects with colour that used the chroma of the screen, made things happen with pixels that I couldn’t even dream of. The way he made things look solid was almost impossible. He already was a Bitmap Brother, he just happened to be at a different company.’

Not that Palace didn’t have its own reputation as an artistic powerhouse. Comicbook legends such as Alan Grant and Pat Mills were knocking at its door, in fact, keen to collaborate. Malone seethes: ‘None of it happened because Palace Pictures bled Palace Software dry.’

The ill fortune of the studio’s parent film company (another war story for when you finish reading this one) meant that despite the considerable success of the Barbarian games, little could stop a bloodbath of active projects. After The Sacred Armour Of Antiriad in 1986, both of Malone’s next big games were shelved. ‘‘Super Thief’,’ reported Games Machine magazine, ‘casts the player as a model of unsullied selfishness, robbing the future for all its worth.’ ‘Astounding Astral Adventures’, meanwhile, attempted to fill a whole galaxy with such rogues.

No fewer than 19 games were in development at Palace, internally and externally, when Patricia Mitchell joined as a producer. ‘It was very appealing,’ she recalls. ‘More like movie production than games and ahead of its time in lots of ways. The quality of the artists’ work was unparalleled, Richard Joseph’s audio was groundbreaking, and external talent like Zippo Games and Sensible Software2 all should have combined into a successful formula.’

‘The difficulty was finding programmers who could craft these elements into playable 16-bit games. The fabulous graphics ate up memory, the processors had a learning curve, and each machine required individual programming to get the best out of the hardware.’

Palace killed its 8-bit projects first, in a bid to cut costs, but the 16-bit install base was too small to fill the void. Furthermore, the games came out late and underperformed. ‘It was the epoch of large publishing houses who often owned the distributors and shaped the market,’ says Mitchell. ‘It was tough for small independents.’

Malone remembers the aftermath: ‘No one knew what was going on, whether you’d have a job one day after the next.’ The writing was on the wall, and Mitchell and Stone used their contacts to see where people could go.

Meanwhile, over by the Thames, the opposite was happening for The Bitmap Brothers: they were diversifying. Artist Mark Coleman was thinking beyond what was next on the slate. He declares: ‘I really did not want to do a Speedball 2. Having done Xenon 2 in the interim, I was in no mood to revisit my past mistakes. Plus, they were talking about Gods, and that got me really excited. I could visualise exactly how I wanted that game to look, and what we could do with it.’

Sat before the Palace copy of Speedball, Malone was considering his next game, too. He remembers thinking out loud: ‘I really need to see these guys.’

Weeks later, he was one of them.

This Brutal House

‘God, it was a hike to get out to Wapping,’ complains Malone. ‘And when you did it was so quiet – too quiet. There was The Prospect of Whitby pub, which was all right because people actually travelled to that one, but that was it. There was a Spanish lass who worked on the top floor of the Bitmaps’ office and had a record label, and she was the only other bit of creativity in that whole block.’

For his first fortnight at Bitmap HQ, Malone was the only person working on the new Speedball. ‘They put me on it just to start doing the characters and figure out the angle. They were like: “Have you played Speedball 1? Right, we want a bigger pitch, double the size.”’

Speaking to Amiga Power in 1991, Eric Matthews explained: ‘We knew we had to make it quite different to be worth doing. The increased screen size was to make it more exciting when you got into the other player’s area – as it is in Kick Off. In the first game you can just throw the ball all the way down the pitch, which makes it far too easy.’ It was, he added, ‘like playing in a shoebox, it’s so claustrophobic.’

For Malone, those first weeks would produce a considerable body of artwork, albeit ‘for my own pleasure. The brief wasn’t to draw lots of pretty pictures, it was to “Give us some fucking graphics.” Things really only started moving when Rob came in.’

Robert Trevellyan, like all programmers, is a problem-solver. And like most computer game programmers during the ‘80s, his first big problem was employment. ‘There was no such thing as a school where you went and “did game development”,’ he explains. ‘Without some kind of contact in the business, or some good luck, it was hard to get in unless you could produce a complete package. I could never pretend or claim to be a game designer, and I didn’t have that friend who could do graphics, like the guys who did Civilization and Railroad Tycoon. There was no obvious path for me.’

The cousin of a student friend, however, worked at Electric Dreams, celebrated maker of Spindizzy, Firetrack, and a host of movie tie-ins and coin-op conversions. ‘I went and I talked to them, and I said: “I have no experience. Tell me what I have to do, what it takes.” They told me to do an eight-way scrolling demo, and that it should take a couple of weeks.’

Loaned one of the studio’s Commodore 64s, Trevellyan bought a 6502 assembler – ‘“You must be confident to spend £50 on software,” said the guy in the store’ – and delivered the demo ten days later. They gave him a contract there and then. ‘It’s not like they had a long list of resumes from people with obvious qualifications,’ he quips. ‘What could they do?’

The project he worked on was cancelled after six months. He was put in touch with The Bitmap Brothers by his supervisor, and the process started again: ‘“Let’s do a demo and see what you can do.”’ So, he produced another eight-way scrolling demo, this time for the ST, ‘with completely uninteresting graphics, but it showed I could make the hardware do something.’ That something just happened to be precisely what Speedball 2 required.

Working from his home on the south coast – he would later move in-house – Trevellyan was given a crash course in 16-bit gamedev by Bitmaps Kelly and Montgomery. ‘Just things like when you first start up the ST or Amiga, the first thing you do if you’re making a game is kick out the operating system and strip the machine down to the bare essentials, and load your code. They had those bread and butter things down already. The core coding for the game, though, and all the AI: that was based on Eric’s vision.’

The original document was this four or five-page pamphlet – drawings, a bit of art, and Eric’s writing. It wasn’t a design, just a flavour. It’s got some things that never made the game, like players on hover-boards, but it’s perfect … I don’t think anyone was going in wondering if Speedball 2 would be any fun.

You see, before Speedball 2 had the perfect pitch, it had the perfect pitch. Product manager Graeme Boxall, then at Mirrorsoft, describes its journey around various offices and desks. ‘The original document was this four or five-page pamphlet – drawings, a bit of art, and Eric’s writing. It wasn’t a design, just a flavour. It’s got some things that never made the game, like players on hover-boards, but it’s perfect. You got it straight away. Everybody who saw it wanted to photocopy it, to show other teams how it’s done.’ Trevellyan adds: ‘I don’t think anyone was going in wondering if Speedball 2 would be any fun.’

Now they just had to make it.

‘We knew the horizontal scrolling was going to be a challenge because that’s why it wasn’t done in the first game,’ says Trevellyan. ‘Vertical scrolling wasn’t quite free on the ST but was certainly cheaper than horizontal. We had to adopt some very tricky techniques, and you can really see what’s going on if you put the ST and Amiga versions side-by-side.

‘You’ll see that the ST version has the same sides and bonus features – the chutes and stuff – but the central area is just a series of 16×16 tiles, whereas on the Amiga there was a nice design to it. We couldn’t do horizontal scrolling with a fully designed graphic at 25 frames per second on the ST, so what we had was values pre-loaded into a whole bunch of registers. The 68000 had 16: eight address registers and eight data registers – so, about 10 or 12 were pre-loaded with values to create that tiled central area. Then, at each offset position of the scroll, you’d load in a rotated set of values and just blast those across the majority of the pitch, picking up the individual graphics for the sides and the ends.’

Malone was plotting all of his pixels by joystick at this point, and there was none better than the TAC-2 (Totally Accurate Controller MK2) by Suncom. ‘It was the best joystick I ever used. It was really clean, and it kicked when you used it.’ One thing he was keen to change, though, if he could swing it, was the money-minded porting of ST graphics to his more capable dream machine, the Amiga.

‘Historically, it was a case of copying the ST graphics straight across without touching them – but I touched them,’ he smiles. ‘Peter Molyneux asked once, “What’s your angle?” I said I just wanted to hide the pixels. I wanted them to be smooth like it’s a comic or a coin-op. I wanted to use every single bit of that palette, so I did the sprites first on Amiga and then they went over to the ST. I held up everyone doing a new floor for the pitch, which is why the Amiga version has that star design. I got told off for it but it was right: the Amiga was the superior machine. Porting from ST wasn’t good enough.’

This stubbornness, he continues, is why the Amiga version of Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe also has more animation for its ball launchers, and better lighting in its management screens. He couldn’t redraw the game from scratch, but the Amiga palette meant he could greatly improve the stippling used to achieve shades of colour.

‘People – journalists – often made jokes about palettes back then. I wasn’t going to be “monochrome guy”. The kids wanted bright and sharp, and I like distinguishing characters, and objects with purpose, by their colours as much as their shape. Speedball 2 was all kinds of blues and cyans, and some purples; that’s as close as I could get to a shade, where I’d have to use purple or magenta knocked down a bit.’ His signature art style, he explains, a kind of flat-line technique with one flat colour and a few shadow layers, was born on the Amiga. Now he uses it everywhere.

The other mandate for the game’s lone stadium was to show more of each character than the strictly top-down original. ‘I really struggled with it,’ says Malone, ‘but I learned the lesson. It’s a bit like isometric but the angle’s like a 45-degree. It’s like taking a box and just opening it out so you can see everything.’

On their journey from ink to pixels, Speedball 2’s characters had already been upgraded to Malone 2.0, less theatrical and more utilitarian. ‘I loved sport for the same reason I loved games: the idea of performing with people watching, where everyone knows if you fold under the pressure. But I hated football, I just watched skateboarding. That’s where the hard shell pad design and the knee sliding in Speedball 2 came from.’

Matthews, meanwhile, had given it a backstory: the sport’s slide into corruption and exile; its underground reincarnation; the emergence of a fresh-faced rookie team. ‘Eric had his gameflow up in his head, and from there it was all logical progression,’ says Malone. ‘I did a few storyboards to show the different title screens and how they worked, and that was the first time I’d really bartered with a programmer: “Can I have this? Surely this.” I didn’t want their feet to slip, for instance, but we never could get that one. It was always my dream on the Amiga to have them walk, but I think it was always quite hard to sync up the four-frame run.’

Handed this ‘proper futuristic basis’ for the game’s second coming, Malone set about not just drawing it, but naming most of it, too: ‘The original expression Brutal Deluxe is a music reference. It’s a tune called “This Brutal House” by Nitro Deluxe, this wicked house tune from the early ‘90s. I came up with a lot of the team names, actually, about 20. “Revolver” was my old scooter club, the most violent scooter club in Suffolk.’ But weren’t they the worst team in the game? ‘Yeah, I don’t know what happened there. Someone must have fucked up the levels.’

Teams are the backbone of Speedball 2: the way they look and act position the game bang on the halfway line between arcade title and sim. This is a treacherous place, maybe even cursed, strewn with the bodies of competitive online games and EA Sports career modes. This game triumphs, though, for two particular reasons: elegance of progression (save-and-spend has never felt so immediate) and visibility of AI (save-and-spend has never felt so important).

Trevellyan explains how all of the key attributes of Speedball 2’s AI are nakedly exposed through its management screens. Values for Strength and Aggression, for instance, are run through a formula whenever a player starts tackling (be it a sliding tackle or brawl), with a random number thrown in for good measure. ‘If you’re incredibly strong and he’s incredibly weak, you’re going to get the ball most of the time.’

The most critical attribute, though – the thing that makes Super Nashwan the scariest team on the fixture list – is response time, a blend of Intelligence and Speed. Regardless of whether it’s singleplayer or multiplayer, CPU teammates are always thinking about position: where they are, where their teammates are, where the ball is, and who’s got it. ‘The bulk of the AI code is getting players into the right position at the right time,’ explains Trevellyan. ‘It makes a big difference to how smart the opposition seems if you simply recalculate those things more or less often. Intelligence also determines the size of the calculation area. They really do differ. It’s not all smoke and mirrors by any means.’

There is some theatricality, though, as Matthews explained at the time: ‘We exaggerated it so that if you’ve built up a player to be fast, he really will be. With most management games – which aren’t the sort of games I’d ever normally play – you might as well have changed nothing, for all the difference it seems to make during play.’

I wanted several female characters – we had a big conversation about drugs, what it would take for a woman to compete in that world – and I got two in, but people thought they were blokes!

Speedball 2 knows that AI doesn’t sell itself. With the right presentation and theatrics, however, it’s what can turn a game into a sport, and the sportsmen into superstars. Nowhere is this clearer than in the game’s management screen, which Malone would rather have had called the ‘gymnasium’: a place that’s more about looks than skills.

He explains: ‘The last thing I did at Palace, along with ‘Super Thief’, was that game ‘Astounding Astral Adventures’. A lot of the characters for that are Speedball characters, that’s what they evolved from. There’s a Laurel and Hardy-type couple in there as well [a debt, presumably, to the aforementioned Sons of the Desert], these fools who are just mechanics. The names – things like Roscopp or Jams – would always come from the faces, or vice-versa.’

Put it all together and, in a blur of matches and management sessions, Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe gives the player a 360-degree view of their team that never has time to fade. By acting like their stats and their place in the 3-3-3 formation, the players identify themselves as Garrick, Midia, or whichever other menace you’ve poached from the transfer market, even when they’re just a swarm of identical heads and shoulders.

‘If someone said, “Give me 50 more Speedball 2 characters, I’ve got a budget,” I’d drop everything, just to show the stuff that never made it,’ says Malone. ‘I wanted several female characters – we had a big conversation about drugs, what it would take for a woman to compete in that world – and I got two in, but people thought they were blokes!’

Lawless, Chaotic, and Fun

Speedball 2 is a very handsome kind of ugly, then, and quite loud about its subtleties. It’s as far from your average game of ball-meets-face as any Bitmap title is from its arcade idols.

Case in point: its intro.

The first few seconds of most games today are exactly the same: screen after screen of idents and corporate logos; a billboard for the sponsors. This has set a toxic trend, and the power and potential of that moment is wasted. It is easy to forget that once upon a time, it acted as a canvas for the developer, to harness the player’s excitement, and to build anticipation.

This was never lost on The Bitmap Brothers.

The show begins in those one or two seconds after the disk stops grinding, when that initial load is done. Everything in RAM is now storyboarded, calculated by man rather than machine. First, we see white letters on black, blinking in like a ticker or a telex: ‘IMAGE WORKS PRESENTS… A BITMAP BROTHERS GAME.’ Pause, fade to black. Then comes the bull-rush.

Malone’s title screen for Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe might be one of the greatest of any videogame: a stadium in a city of endless steel. It’s hard to imagine a better debut for the Bitmap raised on comic books than this single low-res panel, suggesting as it does a world of tyranny and intrigue, and a sport in which everything has changed.

From the speakers: a theme tune which may or may not be techno, might not even be music, but is quite perfectly Speedball. The notes, all angular honks and squalls, pile upon each other in a bid to be heard first. They swerve and skid and and outmuscle each other across three sweet minutes of precision pandemonium.

Rhythm King’s Martin Heath is very clear about this: ‘John Foxx is a fucking genius. He’s an artist from Yorkshire, and he hates Midge Ure.’

Quiet amid the vanguard of electronic music, with work spanning numerous artforms and personae, Foxx is perhaps still best known as the original frontman of Ultravox. Many of his gaming fans don’t even know him by name, but as Nation 12, a short-lived Rhythm King supergroup founded by Tim Simenon, who explains:

‘Kerry Hopwood, who was working with me at the time, doing programming, was a big John Foxx fan. We went to John’s house up in Highgate, and I actually approached him with the idea of him singing on a Bomb the Bass song. But he said, “You know, I don’t really do music any more.” He was doing all this photography stuff. “But I do have a few demos I can play you.” And they were brilliant. I thought that maybe we could just do something with those tracks, turn that into a separate project.’

The group produced its first track, Remember, before Simenon invited Shem McCauley (then performing as DJ Streets Ahead) to work on a second, ‘Listen To The Drummer’. The trio didn’t last long – Simenon left to produce sophomore Bomb the Bass album Unknown Territory – but McCauley kept Nation 12 going, bringing in ex-The Fall member Simon Rogers to help Foxx produce an EP. That’s when Heath came knocking. As he recalls: ‘John was fascinated at the idea of young gamers producing their own software from scratch without anyone telling them what to do.’

In fact, as Foxx himself puts it, this democratisation was happening everywhere. ‘You were beginning to see a point where musicians could have their own studios for the first time. Artists and designers could have their own machinery; so could animators, writers, gamers … The potential seemed endless.’

‘I remember at the time becoming conscious of a new generation taking computers and games and even coding as their primary cultural currency – the first full generation to do that. This was a seismic shift away from the way music had dominated previous generations. Now it was all technology-based – so this generation predicted the future perfectly.’

‘I’d read Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s and realised that what he predicted was finally happening. It was a technological revolution and we were all at the start of it. You found yourself there purely by coincidence, by accident. That’s how I really like things to happen. It was just like landing in London and punk beginning to happen some years before. A new world was opening up – a bit like being in the Wild West. Lawless, chaotic – and fun. Who could have guessed it would all get colonised by corporations?’

It was a technological revolution and we were all at the start of it. You found yourself there purely by coincidence, by accident. That’s how I really like things to happen. It was just like landing in London and punk beginning to happen some years before.

Foxx was brought into the Wapping studio, given the spiel, and shown some graphics sequences. As he describes it:

‘The Bitmap Brothers philosophy was never articulated, it went without saying. You either got it not.’

‘They were enthusiasts. They understood their own generation because they shared all those fundamental enthusiasms and could see clearly what the potential was, and how it needed to be realised in order to get maximum blast from what they were making. It was embodied in everything they did.’

The music was sequenced at Foxx’s home. The Bitmaps had given him a ‘sound box’ programmed with all of the sounds they had available at the time.

His mission, as far as he saw it, was ‘to make something that could stand as a sort of annexe to the game, something of equal effect and quality – as far as you could. The songs were always intended to evoke a world that the games might take place in. They set the stage and the atmosphere, just as a movie theme sets up the world of the film. They were the gateway.’

As with Simenon and Xenon 2’s ‘Megablast’, though, Nation 12 would need a translator for the new world of code – someone who, as it happened, had only recently learned the language himself.

Richard Joseph was a trained musician and grade eight vocalist when he joined the prog band CMU for their second album. ‘He was fantastic, genuinely brilliant,’ begins longtime collaborator Michael Burdett. (Bitmap fans will recognise him, too, but more on that in a moment.)

Joseph then went solo and signed a recording contract with EMI which, as Burdett remembers, gave him ‘a substantial amount of money. He made really wonderful stuff, a kind of cross between Al Jarreau and Steely Dan, if you like. But it was a funny time in the music industry: punk was coming through, and both his record label and publishing house started showing a lack of interest.’

Stymied by a contract which meant he couldn’t record solo material elsewhere, Joseph used the EMI money to buy a recording studio in Chorleywood, which he rented out for £35 per day. He formed a band, Baghdad Five, and put out a single called ‘Loving Infection’. Burdett laughs: ‘The mid-’80s was definitely the wrong time for that one.’

Now at something of a loose end, Joseph saw an advert in Melody Maker for someone to soundtrack computer games. It was Palace Software, where Joseph would lend his talents to games like Stifflip & Co and Barbarian.

‘Rich’s girlfriend at the time, Alex, provided a lot of female voices for games,’ says Burdett. ‘Once, he filled a wardrobe with pillows and a microphone, and he put her in it. She was coming out with all sorts of noises of alarm and whatever, but Rich wasn’t convinced they were realistic enough. So, every now and then, he’d throw open the cupboard door and swing a punch – missing, obviously – just to get the correct level of fear.’

‘Palace did everything in hex, and Rich didn’t know that. He was working 22 hours a day learning to code and program, and I don’t quite know how he did it. He was a fantastic editor. You couldn’t have music and sound effects at the same time with some of the early hardware, and he was very good at using the polyphony of things. I always thought of him as a bit like a Frank Zappa or Prince.’

Foxx agrees: ‘He was excellent. The only thing I occasionally regretted was he tended to straighten out some of the more jagged and eccentric timing I deliberately used in places. But I respected his judgement – it was teamwork, after all.’

Foxx and Joseph’s work on Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe is indeed complementary. That ‘polyphony’ of the game’s sound effects is hardly melodic, but it is definitely musical. It takes a goal or an injury, either of which makes the crowd noise decay, before you appreciate the ear-bashing you get the rest of the time. The effects, all metal on metal and pulverised human yelps, are so savagely cut as to sound surreal; but the result is an unbroken, hardware-defying din. And then, from the terraces, a certain someone shouts ‘Ice cream!’

‘It was my idea,’ confesses Burdett, who happens to have voiced almost all the Bitmap Brothers’ games. ‘Rich had got a room at Pinewood Studios, which without a doubt would have been through family contacts.3 I went off to write music for television, and Rich stuck with computer games, but we remained great friends. We’d still get together, and when we did it would always be: “I’ll tell you what I need!”’

‘There was a script of two or three lines for Speedball 2: things like “Get Ready!” I’d do those and then we’d look at each other because it had only taken 30 seconds. “So, what else?” I feel embarrassed to say it now, but we tried to imagine what else there’d be in a crowd scene, and I parodied the Monty Python sketch with the salesman in the cinema. “Albatross!” Obviously, we weren’t going to use that, so, to my shame, I put on the Italian-American accent and went— I’m not going to do it for you now.’

Full-time

A star performance in the making for the Bitmaps, Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe wouldn’t have been Speedball without some injuries. Its final months saw Malone tasked with bolstering the art of Cadaver, leaving most of the punishing QA work to designer Matthews and programmer Trevellyan. It was a period famous for killing dozens of Suzo ‘The Arcade’ joysticks. This was no mean feat: these controllers were so tough that they could probably do a bit of killing themselves if swung at another player.

‘It’s one of those games where it feels like if you push the stick harder, the characters should move faster,’ notes producer Simon Knight. ‘And you were desperate to win. The joysticks took a pounding; if there was a lucky goal, you’d take it out on the hardware. We went through a lot of them, but [The Arcades] were definitely the best. I remember spending hours and hours pummelling one when we were doing Xenon 2.’

But joysticks weren’t all that broke during this period, as Trevellyan reveals: ‘People didn’t make as big a deal of it with The Bitmap Brothers as they did with id Software, but both adopted the same philosophy: It’s done when it’s done. I’d hesitate to use the word “genius” to describe a game designer, but Eric was extraordinary in terms of knowing how to balance a game so it was just so. He had great vision, but tuning it is what made the difference to the success of The Bitmap Brothers’ games.’

Mike Montgomery adds: ‘Most QA was the job of the publishers, but we didn’t trust them. Publishers think they can design games, but at that stage of development they had no idea at all. They’d try and change the odd thing, but we’d always very strongly say, “No, we know what we’re doing.” So, we were late on everything. The money was different back then, too; we paid for a lot out of our own pockets and hoped the royalties came in and fixed it all.’

With publisher QA in its early infancy, this handful of developers weren’t just gauging whether the game was good for them; they were also gauging whether it was good for an audience they had next-to-no contact with. Yet, as Trevellyan explains: ‘There were difficult games, and there were difficult games which got bad reviews for it, but I don’t think you’d ever get that from a game Eric tuned. Speedball 2 was hard to beat but you could get a long way through it and beat a lot of teams.’

‘As a pretty green guy, though, that endless tweaking at the end to get it just right almost drove me crazy. It took a lot of time and playing. I kept thinking, “Well, the game’s done now.” But no, there were months to go.’

As Boxall sums it up: ‘Eric made the games great, Eric made the games late.’

Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe was finally sent to mastering, and Trevellyan wouldn’t work again with the Bitmaps until The Chaos Engine 2. ‘Naively,’ reflects Trevellyan, ‘I said I didn’t want to work with Eric any more – and I regret that to this day.’

‘He is very charming and charismatic, and you want him to like you. When you’re on his good side, you’re basking in that warm glow. I didn’t fall out with him but, having said that, I was taken at my word. I didn’t work with him again, and it was a mistake I made early in my career which luckily didn’t cost me my career.’

The game was released in 1990 to a rapturous reception, to the surprise of pretty much no one. ‘The entire thing simply oozes a class and quality that is rarely found,’ declared C+VG, awarding the initial ST version 95%. ‘Dan Malone’s graphics are nothing short of spectacular.’ Two issues later it would bump that score to 97% for the Amiga version, recognising the new pitch and sound effects. 96% in Zzap!64. 95% in CU Amiga, which found ‘absolutely nothing to fault.’ ‘It’s the football game that could only ever exist on a computer screen,’ remarked Amiga Power for the budget release, by which time the game had scooped InDin, Gen 4, and Golden Joysticks awards, and been ported to numerous computers and consoles, both 8- and 16-bit.

To the smug satisfaction of Amiga owners, though, it only really belonged on one. Speedball 2 is a definitive Amiga game – some would argue the Amiga game. It’s an experience made by and for artists, audiophiles, and those who like their arcade games to have a certain cinematic heft. It’s not ‘wrong’ for other platforms, just off, like so many coin-ops and console games ported the other way. It’s not fast like a Hurricane Kick on the SNES, or a Spin Dash on the Mega Drive, but like a fist through an inch of steel. A testament to the Amiga’s power, then, but also to its quirks – its identity as a piece of hardware.

In August 1990, Gary Penn asked Matthews if Speedball could ever become a real-life sport (a notion teased by its celluloid ancestor, Rollerball, too). ‘It’s too tough,’ scoffed the Bitmap, before offering: ‘The strange thing is, now that we’ve got [the game] behind us, it’s almost like it really does exist.’

This is because The Bitmap Brothers, a team with almost perfect stats – Programming, Vision, Tenacity, Brand – added a good few points to its Fiction when it picked up Dan Malone.

The comicbook artist from Ipswich never did work for 2000AD, but he drew his megacities and his perps as title screens and sprites. Together with Joseph’s audio, his work sends the imagination high up into the nosebleeds of the stadium, through the unseen ranks of the transfer market, and out into the slums and boardrooms of Planet Speedball.

We’re there – like it really does exist – in a Bitmap Brothers universe.

Footnotes

- 1 Such was the familial nature of Britsoft and its press during the ’80s that, for Penn’s birthday, Schembri and Malone gave him a tape containing the custom-built ‘The Sacred Armour of An-todger-ad’. The former journalist explains: ‘Dan redrew all the graphics so the hero walked around with a giant cock. A real birthday gift, that was.’

- 2 Palace published Sensible’s Shoot-‘Em-Up Construction Kit (1989) and International 3D Tennis (1990), and Cosmic Pirate (1989) by the Pickford brothers’ Zippo Games.

- 3 Joseph came from an influential filmmaking family. His brother, Eddy, is a BAFTA-winning sound supervisor; his brother Pat owns visual effects house The Mill, which won an Oscar for its work on Gladiator; his father, Teddy, was a highly successful producer during the ’60s. ‘You’ll often seen his name on the end of Michael Caine films,’ says Michael Burdett.