Generation Tony Hawk

How a genre busting PlayStation game shaped the UK skate scene

It’s late summer 1999, I’m 15 years old and I’m hearing punk music for the first time. Eventually I’ll find my way through the genre amongst mislabelled Napster downloads, a 13-track capacity mp3 player, the tape-to-stereo jack in my older friend’s car, and Fat Wreck and Vagrant samplers handily filed under ‘P’ at HMV. But right now, it’s late summer and the Dead Kennedy’s anti-cop song ‘Police Truck’, with its thrumming bass line and thrilling riff, is ringing through my mind. This is the song that opens Tony Hawk’s Skateboarding. This is what caught me, but for hundreds of thousands of others, it was the video footage. It was seeing world-class skateboarders on their TV for the first time, in a way that was for many back then – in sleepy, pre-internet English suburban villages and towns – a revelation.

Like many of the girls from the late ’80s and early ’90s I know in videogames, I didn’t have a console of my own; it belonged to my brother. It wasn’t a conscious thing on the part of my (passionately feminist) mother; it was just, he asked for them, and I didn’t know they could be ‘for’ me. My experience of the era of commercial games pre-2003 (when I bought a GameCube at university), therefore, extends mostly to those with integral multiplayer experiences, whether built-in (Goldeneye 007, Mario Kart: Double Dash, Beetle Adventure Racing), or games that built a community or audience around a spectacle: exhibitionist free-play levels that allowed you to create your own competition, such as Tony Hawk’s Skateboarding (otherwise known as Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater in the US, and Tony Hawk, from here on in).

The Tony Hawk games were my first contact with both the world of skateboarding and punk music. Without them, I wouldn’t be the person I am today, in many ways – from my interest in skateboarding and punk music, to less obviously connected parts of myself such as my photography, and many friends. These things all eventually come back to my experience playing the Tony Hawk videogames.

My 13-year-old brother and his friends invited me to play Tony Hawk. I was not awful at it. I didn’t get to practice though, so I wasn’t great, but I jumped at every opportunity to play because the music in it – the music was something that I couldn’t get anywhere else. I used to think, as I retuned my radio from BBC Radio 1 (I discovered John Peel too late) to BBC Radio 4 – that there must be something wrong with me, because I didn’t like pop music, or wishy washy indie. And then, as if from a different world, the Dead Kennedys; alive, so alive and raw and aggressive and different to everything that had come before, for me, in a village in Lincolnshire. But for many others, including my brother, it wasn’t the music. It was a new skateboard and scraped knees, learning to ollie on the pavement outside our cramped cul-de-sac. It was the increasingly baggy trousers we all wore, and our pairs of ripped up Vans.

On being invited to write something for Read-Only Memory, I instantly thought back to that moment, the Tony Hawk opening credits. But I also thought that I didn’t want to write about my journey into punk (how that moment among others helped open a world of music in which I participate to this day). Instead I wanted to find out – did it happen to you too? I wanted to investigate the bit I knew less about: all of the kids and teenagers who picked up a board instead of a mix tape. Did it do for skateboarding what it did for me and punk music? What happened to skateboarding in the wake of Tony Hawk? Did Tony Hawk create a new generation of skateboarders? Did the game – a game that set out to replicate it – change skateboard culture?

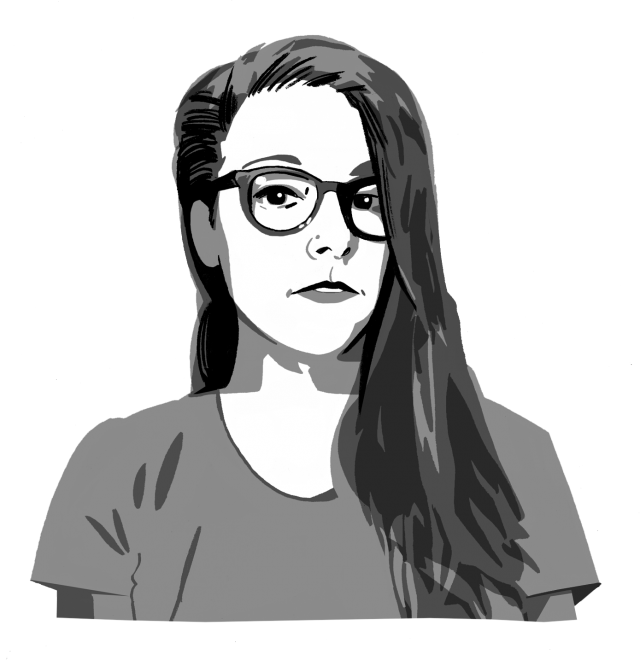

So I sought out three particular people to ask these questions of: Dr Patrick White, a lecturer in sociology at the University of Leicester who has been skating for nearly 30 years; Andrew Waterfield, who works for Universal Music, has run punk zines and written for PunkNews in the past, and who got into skateboarding around the same time as Tony Hawk was released in 1999; and Elissa Steamer, a pro skateboarder featured as a playable character in the first Tony Hawk game. These three conversations were an attempt to trace the effect of Tony Hawk on skateboarding, as well as considering how skateboarding’s history and qualities were translated into the world and mechanics of Tony Hawk. One skateboarder pre-1999, one skateboarder young enough to have been affected by the game, and one of the skateboarders in the game.

At the time the first game came out, I was hugely interested in both games and skate culture but didn’t actually skate. Playing Tony Hawk got me off my arse and down a shop to buy my first deck. I really wish I was cooler than that but I wasn’t! Without Tony Hawk, I probably never would’ve skated at all.

You may notice that this article is also accompanied by comments on the experience of first playing Tony Hawk as written by players themselves. These comments reflect the fact that skateboarding is a pastime (it’s kind of complicated and usually wrong to call it a ‘sport’) that grew from the bottom up – when the markets and business have got involved in skateboarding, they’re following, rarely leading. It was the reject surf kids who carved a space for boards on the streets, experimented in pools, built new moves. New technology shifts it a little – the introduction of polyurethane wheels, for example – but they were made for roller skates, not boards, to begin with. Board shape experiments largely came from skaters themselves; the skate shops and video makers and zine editors were all skateboarders first. Sponsors and TV get involved, and it’s used as a byword for street cool as it passes briefly into the mainstream eye, but just as often over the past near half century, it’s been an under the radar urban practice, invisible to all but those who practice it. So I invited in the voices of people who played the games, to have their say too.

The quotes were gathered by using a self-selecting survey and spreading it online using Twitter and Facebook groups. Particular encouragement was given to make the survey welcomed women and minority gender identities, as well as people of colour, but it’s worth stating that the responses are primarily (81%) from men. As for the rest of the makeup of respondents: most were aged 26–35 years old (55%), only 8% weren’t white, and 22% described sexualities other than straight.

Part of the history of skateboarding is a mix of rebellion against the status quo, and yet also, within the community, tied together (like in many ‘extreme sports’) by a privileging of a white hyper masculinity which renders women, POC and openly queer identities a constant minority. At the same time, it’s worth noting that in other cultures, completely different demographic makeups flourish. For example, at the beginning of our conversation, Dr Patrick White brings up Skateistan – an NGO project which attempts to be ‘a tool for youth empowerment in Afghanistan, Cambodia and South Africa’ through the medium of skateboarding. White explains that,

‘In Afghanistan it had absolutely no reference point for skateboarding, it was completely new, there were no cultural references, and as many, if not more girls from the schools started skateboarding […] it’s interesting for me what happens when you start from a cultural blank slate.’

One is not born, but rather becomes, a skateboarder.

Game play

Tony Hawk largely represents the street skate style that rose to prominence in the early 1990s, the second wave, post-Z-Boys1 , after the first boom and the ’80s bust where it fell to the underground. Skateboarding, which originated in the US, grew popular in the surf culture and emptied pools of California, and was steadily revolutionised (as noted above) by the introduction of polyurethane wheels, as well as revisions to the design of the trucks, board dimensions and other technologies (for example ‘slicks’, boards with thermoplastic on the bottom of the boards facilitating boardslides 2 ).

There are elements of vert and pool skateboarding in the Tony Hawk series, largely due to the game needing to provide a variety of locations – it used moving from location to location and an ‘unlock’ mechanic as extrinsic motivation to progress through the game. Games excel as an environmental form, and allowed Activision to carefully recreate the kind of places and spaces where skateboarding actually happens. As such, they sought variety, meaning a melding of different terrains. There are purpose built skate parks, as well as well known cities and specific neighbourhoods claimed by skateboarders and ‘general’ skateboarding spaces like malls and abandoned warehouses.

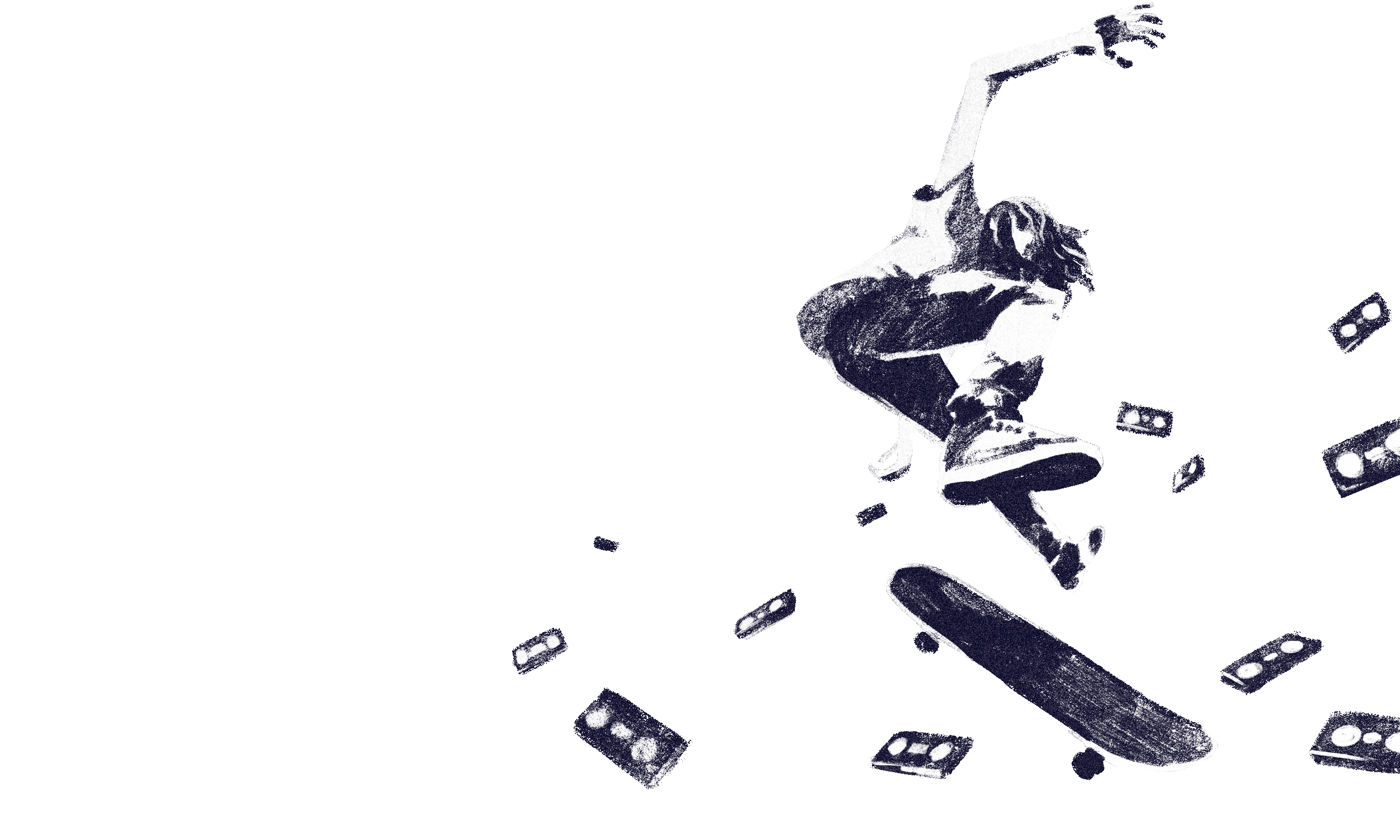

The initial game focuses on points awarded for tricks (more points for more longer, fluid runs of connected tricks), and unlocking mechanics (collecting the letters S K A T E, hitting certain trick and point targets). But instead of translating the in-game achievements into money (like later Tony Hawk games), the original game uses ‘tapes’ as a currency for progression instead. The later Tony Hawk games’ move to cash turned being able to get board upgrades and new clothing into a more mainstream exchange, while Tony Hawk’s first exchange mechanic of ‘tapes’ speaks far more interestingly to the currency of skateboard culture in that pre-YouTube era.

I think I’ve heard that there was a bit of backlash from the traditional/older/more sincere group of skaters that were annoyed that all these kids bought skateboards to kickflip in front of girls and roll into dumpsters because they saw it on Jackass with no real respect for the ‘history’ of this, like, ten-year-old activity.

As you trace the history of skateboarding up to the ’90s it becomes clear that the points system is based on a combinatorial principle, which only really emerged in skateboarding competition culture around the end of the 1980s. Borden in Skateboarding, Space and the City credits Eddie Elguera’s 540° ‘McTwist’ as a turning point (lol), quoting Jocko Wetland in Thrasher Magazine, in 1987, who wrote about watching him perform the trick:

‘Skateparks and ramps [provide] a theatre for the display of skateboarding in which skateboarding and its body becomes spectacularised. This is immediately evident from the new moves that skateboarders invent within these terrains.’3

‘In that moment when he was flying with his top and bottom reversed, everyone who was watching the pool saw something so amazing as to be unbelievable … Things had changed. In an instant a new dimension had opened up.’

As skateboarders spent more time in the air, more time finding out what was possible on flexible, purpose built wooden ramps, as they moved out of concrete pools and parks, they began to push at the boundaries of how much they could fit into each fluid move. That’s the culture that gave rise to Tony Hawk himself – the phenomena of skateboarders who rose to fame for pushing at the edges of the practice. And that’s what informs the central mechanic of the points system in Tony Hawk.4

And one last note on how Tony Hawk translated the skateboarding culture of the time into a videogame artefact: Tony Hawk is actually is pretty hard. What’s more, you fail a lot. The impact of slamming a trick, the sound the skater makers, the impact it has on the flow of your playthrough, is all significant. ‘Skateboarders spend perhaps more time than any other sports practitioners actually failing to do what they attempt’.5 In making a game out of such a practice, Activision discovered a strong match for the qualities of teaching and learning in games – in a pain-free environment, games tutorialise your failure as a path to learning. On a real skateboard the stakes are higher, but it holds within it the element of Csikszentmihalyi’s flow – of the moment of absorption you feel in pushing hard at the edges of your capabilities6 – that directly translates to a videogame context.

Elissa Steamer, the only woman featured in the original Tony Hawk game, (and who still skates whilst running Gnarhunters.com) whose career is often credited as having been given a significant boost by the visibility the game gave her (as it did all of the skaters featured) talked to me about how Activision worked with skateboarders to make the game. They actually drove it around and demoed it in skateboarder’s garages:

‘I first saw a demo of the game in Jamie Thomas’s garage. He said I think they might want to get you in it also. Maybe the next day Mark Waters called me up and told me about it and got me in contact with the Activision people.’

Like most skateboarders, it’s a way of life for Steamer. She started skating just after the Z-Boys era, in the early ’80s. She explains how it shaped her and how she moves through the world:

‘It’s kind of like an education or a way of learning. If you grow up skateboarding, you just kind of think differently and navigate through the world differently. You may be comfortable in situations where someone who’s not a skateboarder may not be. If I have a friend who is trying something new and they haven’t skated, I may pay extra attention to them or be more cautious. If they are skateboarders I just give them basic instructions and let them be. I think, “they’re a skateboarder, they’ll figure it out.”’

It’s a language and a way of learning – just like a videogame controller and the understanding that failure is part of the learning process are inherent to most videogames. Actually being put in the game was straightforward, Steamer explained:

‘Working with them was simple. I just drove to the Valley and they took my picture. [Then] they asked about tricks and stuff. Like what I would want my special move to be.’

I ask Steamer what effect being included in the game had on her specifically, and she replies enthusiastically:

‘I thought it was sick! I always played videogames growing up. 720°; Skate or Die; Town and Country. Being included in the game had a huge effect on me. All of a sudden people who knew nothing about skateboarding other than the game knew my name and likeness.’

The game was a distributed medium way before skateboarding made it onto mainstream TV, and in an era pre-pervasive internet access.

5,000 miles away, in middle of nowhere places in the UK, eager teenagers put the disc into their PlayStations, and girls like me chose to play as the person who most looked like them. Rarely would I get to play as a woman. I ignored the jeers, and luxuriated in the opportunity.

Culture Shift

One of the final questions I ask of Steamer is how she thinks (if she thinks) Tony Hawk affected the culture of skateboarding that followed the launch of the game.

‘I think the series definitely brought skateboarding more into the eyes of the mainstream or people who normally wouldn’t think about skating. I think it had both positive and not so positive effects. People would just assume that you could skate the way the videogame did. It probably changed the way people thought about skating. Now all sorts of kids are doing Manny Ledge rail combos and stuff. Pretty crazy really.’

There’s lots to unpack from her response – first the phenomena of the game and bringing new kids to the pastime. The ambition it gave people – an unrealistic ambition that nevertheless was part of pushing what people could imagine was possible. Then there’s that notion of ‘the mainstream’, which skateboarders always wrestle with in the ‘boom’ parts of the boom and bust cycle which is an intimate part of skateboarding’s rise and fall from prominence.

As a young English skater it taught me a lot about American skateboarding and punk music beyond the Xtreme channel and the X Games. From what I remember the image of skateboarding around that time was starting to get pretty glossy, even though it was deemed quite a dirty subculture. The games felt quite real in a way, beyond graphics and gameplay.

Before the internet connected us without a second’s thought, the threads of connection between skateboarders were fanzines, magazines, VHS, the people you skateboarded with, and the mail system, which alongside skate shops often operated as hubs through which these things were proliferated. Because Tony Hawk was made with skaters, it was just authentic enough to feature the actual places you read about and could see in the videos you collected in-game.

Tony Hawk connected into the pre-existing network, but through the distribution of the game console, that grumbling grey box in the corner of so many teens’ living rooms, it also gave a whole new group of people a taster of the community in form as well as content. Tony Hawk created a multiplayer community for an ostensibly single-player game. It connected to the theatre of skateboarding: it suggested that a shared skateboard space is not only a place to learn and do, but also a place to watch. I use the word ‘theatre’ here as Borden does in Skateboarding, Space and the City:

‘Skateparks and ramps [provide] a theatre for the display of skateboarding in which skateboarding and its body becomes spectacularised. This is immediately evident from the new moves that skateboarders invent within these terrains.’

The making of Tony Hawk also (as Steamer suggested) represented another oscillation in the relationship between the countercultural and the mainstream in skateboarding. This oscillation is something that both Andy Waterfield and Dr Patrick White often brought up in talking about their experience of skateboard culture and history – each of them representing either side of the Tony Hawk watershed. Dr White doesn’t specialise in the study of subcultures, or ever write about skateboarding, rather I approached him as someone with a sociological background, but one – most importantly – who has been a part of the UK skateboarding scene since before Tony Hawk was released. He immediately begins to talk about the shifts from underground to mainstream7throughout the history of skateboarding:

‘Until Tony Hawk [the skateboarder] and the X Games and pro skaters, the corporate world wasn’t interested in skateboarding, because it couldn’t see how it could make any money out of it. […] No one was in it for the money. […] kids started skateboarding to get away from their parents just like they started punk bands. Now, you go down the skate park and there’s dads bringing their kids down there, coaching them, taking them around. […] And that’s so, kind of, anti-skateboarding to me.’

Tony Hawk was part of the late ’90s, early ’00s mainstreaming of skateboarding, Activision thinking that they could make a profitable videogame out of it – and their choosing to use key people and places in order to speak a language of para-authenticity – didn’t come out of nowhere, it came on the back of a mainstream rise. Think of things like the X Games (which began in 1995), and the rise of sponsorship deals from non-skateboard brands, for example. But more so than the televising of skateboarding (which was much less likely to reach the 4–5 terrestrial channel standard of the UK), Tony Hawk, in labelling the tricks, in pushing you to string together more and more, to push the limits of combinations and discover new ones, also gave outsiders a kind of literacy with which to read skateboarding; an entry point into it. However, in recording something, you also trap it. It becomes a discrete thing. Dr White talks about how trick names in particular became fixed things in a way that he attributes to Tony Hawk:

‘I can tell people who started skateboarding after they played Tony Hawk because they have different names for tricks. So, when one-footed ollies came up, for a little while in the magazines they have transitory names. You have tricks that have names temporarily that change, and people called them Ollie North for a time because [Oliver North was involved in a political scandal in the late 1980s]. But that went, and nobody really called it that for ages, and then when they did Tony Hawk they kind of revived old trick names, or trick names that weren’t really current or weren’t really cool, but all the kids playing Tony Hawk thought they were the trick names. So there are people I know who’ve been skating for a really long time who started skating after they’d played it, and they say ‘Ollie North’ or something and I just cringe. Or they don’t know the difference between a bail and a slam, because it gets it wrong in Tony Hawk.’

Tony Hawk captured and in some ways also fossilised the culture, encoded it in one form, rather than leaving it fluid and local to each sub-community. White talks about this as a dividing line for him – the names you give tricks can tell him when you started skating, if Tony Hawk was an influence on you. And of course since then skateboarding has changed again, moved on; in an internet age, there are so many skateboarding videos and blogs within easy access, skateboarders who took up the pastime because of Tony Hawk stand out like a ring in the flesh of a tree, as of a certain time, drawing on a certain set of resources:

‘These people, they started skating in their mid teens so, you know, they’re probably getting on for 30 now, and that’s a defining line for me, the, kind of, pre- and post-Tony Hawk. I mean, now, for people starting skating now, it’s irrelevant, because skateboarding is everywhere and it’s just like mainstream culture, and it’s just another thing.’

That’s important – phases that can be observed, leading to a mainstreaming of the culture which you could link to the profligacy and accessibility of skateboard culture now – the fashion, the shoes, boards you can buy from Argos, communities and videos at your fingertips as the internet weaves us together – but this also isn’t new, just more. Photography and the moving image were vital in the propagation of new moves and styles, in the 1980s when home video technology allowed skaters themselves to make and distribute their own skateboarding videos – from home-video quality to the highly professional videos like those of Powell-Peralta.

I can only speak as someone who experienced it in a small town culture but I feel like it was a bridge between people who did skate and those who were interested. It was played a lot as a shared experience, groups of friends passing the controller between them. I’d say it was definitely the influence for a lot of people I knew to take up skateboarding. A definite positive and bonding influence.

Tony Hawk is notable because of the para-authenticity, where other non-skateboarder led media have used skateboarding as a shorthand for a kind of urban underground. Tony Hawk was significant because of the variety of places, and the diverse range of characters. In providing diverse characters, not only does the game allow you to play as your favourite, it helps you discover other less well known skaters, and represents the diversity of skill and style. Borden writes that:

‘Style is notoriously difficult to define, and while some see it as an “economy of motion”, ultimately for many skaters it was “more an attitude than a technique … something more akin to a dance” and embedded within the smallest of actions.’8

Tony Hawk was part of changing what was conceivable. In capturing the activity, it changed the activity itself. And finally, in being a part of the late ’90s and early ’00s boom, it also changed who could participate, and how they could continue to participate in skateboarding. Dr White explains:

‘Tony Hawk, it’s allowed skaters to make some money out of skateboarding. […] I think it raised the awareness of skateboarding and brought more people into skateboarding. But skateboarding culture is incredibly resistant to outside change. […] it was the awareness which was important […] because basically it couldn’t go on like it was going on in the early ’90s. It wasn’t sustainable. People couldn’t make a living off it.’

A new generation

Andrew Waterfield is one of the people who came to skating in the boom era that included Tony Hawk. He now works for Universal Music, as well as having run punk zines and written for PunkNews in the past, and is a skateboarder from the UK who was intimately affected by the Tony Hawk series. Like Dr White, Waterfield is careful to not overstate the impact of Tony Hawk alone. He explains that:

‘The vast majority of people that played that game never took up skateboarding, in much the same way that the vast majority of people that play FIFA don’t join a Sunday league. But it gave them a context for understanding stuff, and it made a lot of these skaters household names, which gave skateboard culture a shot in the arm and led to the early 2000s boom in skateboard culture.’

And he enthuses about how at the time, learning to skateboard alongside Tony Hawk gave a particular connection to the mechanics of the game, a particular and intrinsically rewarding relationship between the freedom of both spaces; the street and a board, and the open-world feel of the Tony Hawk stages.

‘The gameplay was radically different than anything else that existed. Like, there was the Downhill Jam mode in the first game, which was sort of a race level, but it was not a racing game. Apart from maybe Grand Theft Auto and a few other procedurally generated games on other platforms, there weren’t really open-world games. The Tony Hawk games gave you two minutes and an arena, and went, “Alright, do what you like.”’

He also talks about how Tony Hawk connected him and his friends, in their quiet Leicestershire town, to that global (albeit largely western) community of skateboarders.

‘We were almost entirely alienated from skate culture which is representative of how skate culture’s relationship with the wider culture works, or at least worked then. Like, there’s skate culture, and then every so often there’s the fad when popular culture gets hold of skate culture and goes, ‘Here’s something we can sell to the young people. […] the Tony Hawk games-, even though they were a way of selling skate culture to kids, they carried enough legitimacy, like, they had enough names involved, they had the music down, there were real parks, real spots, and the mechanics of the game were focused on skating as expression. It was the lesser evil of those attempts to get people on board. It felt more like someone was welcoming you in.’

It made me feel like maybe there were other weirdoes out in the world, even if they were possibly all dudes. Still, would have loved it even more if there’d been more lady characters though, of course! The only other thing that made me feel similar was the TV show Daria.

A final observation that could be made, is that this kind of ‘boom’ period – although it’s a time of shifting authenticity, and of pinning down and fossilising what came before, it’s also part of bringing new blood into the scene; a part of it growing in new directions. Tony Hawk and the boom of the 2000s (it could be argued) was part of the shifting ecology of the community. Economists are fond of talking about ‘creative destruction’ – how the end of one state is the progenitor of the other, that life in an economy (and you can have economies of people, not just currency) is vital; stay the same, and you will die. Waterfield expands on this.

‘The boom and bust cycle isn’t always healthy, but it helps keep everything ticking over and it opens up skateboarding to a new generation. It sticks it in people’s faces and goes, “Here’s a fucking thing that you can do,” […] occasionally punk and skateboarding get huge and then kind of disappear back into the background again, which is kind of how we like it, because it’s healthier for the scene as it is to be self-sufficient, but it’s also super unhealthy when the scene becomes insular and you’re not getting new blood in, and if you’re not getting new blood you’re not getting new ideas, which is where the weird conservatism comes in.’

The most unmistakable thing, evident in all of the people who responded to my survey, and in all of the people I spoke to; including Steamer, skateboarder in the game, White, who skateboarded before the game, and Waterfield, who is part of skateboard culture because of the game; is that it’s not just a thing they do, it’s a thing they are. There’s not the division you get in other forms; between art and artist, writer and reader; there are just skateboarders, do-ers. As Waterfield explains:

‘It’s about doing the thing for its own sake, which is kind of what games are for. Like, it has more in common with a game than a sport. And even when you’re playing against each other on, like, the Horse mode and stuff, it’s just fucking fun. And that’s all right.’

That’s all right.

Videogames are culture. Culture affects how they are made, what they depict and what assumptions build them. But in turn they shape us, they are made of and they become culture. It would be hyperbolic to suggest that Tony Hawk changed skateboard culture in the UK on its own. But through a specific correlation of situations – separated from the cable TV of the US, and from the progenitor cultures of California and surf America, before the era of easily distributable video and high quality images – for many people in the UK, Tony Hawk was part of a watershed, part of the late ’90s to early 2000s boom, a brief foray into mainstream culture that receded and brought new blood back with it.

17 years ago I heard the Dead Kennedys for the first time.

17 years ago Patrick laughed because all the kids were suddenly giving tricks these ancient names.

17 years ago strangers in the street recognised Elissa as a skateboarder.

And 17 years ago, 17 years before they would answer a stranger’s online survey about how Tony Hawk changed them, Chris, and Siobhan, and Kate, and Mark, and Milo, and Alex, and Andy, Shi, Matt, John, James, Gareth, Euan, Joe, Connor, and Josh got their first glimpse of a different world.

It changed us.